“Gregg Allman proposed to Cher here,” reads the plaque at the Downtown Grill.

Nearby, “Little Richard often performed at Ann’s Tic Toc,” a nightclub that openly cultivated a LGBTQ crowd even in the repressive 1940s. And around the corner, Otis Redding made his volcanic debut at the Douglass Theatre, which is surrounded by a Hollywood-style “Walk of Fame” honoring several Black artists.

Move over, Daughters of the Confederacy. Commemorative signs in downtown Macon just got a lot funkier.

Rock Candy Tours, working with other civic partners, has blazed the Macon Music Trail with 43 markers – and more coming — to showcase the city’s storied and tuneful history. You can walk it or drive it, with or without a guide.

“Nowhere else in the world has a soundtrack like Macon,” says Jessica Walden, who founded the tour group with her husband, Jamie Weatherford. “We’re big believers in using these stories and landmarks to inspire — not just the music but what it stood for. It changed the world. It was here in Macon, in a deeply divided, segregated South, that artists catapulted into the mainstream, against all odds, and integrated audiences. What happened here was the ultimate lesson in diversity and inclusion. If our walls could talk, they would sing.”

It is impossible to imagine modern popular music without those roots in the navel of Georgia. Little Richard is widely regarded as the “architect of rock n’ roll.” James Brown cut his first record here and invented funk. Otis Redding honed his distinctive vibrato to “worry a note,” as he put it, and define soul music. Then came Capricorn Records and its development of guitar-shredding Southern Rock. Two members of R.E.M., William Berry and Mike Mills, grew up here.

Macon, with its columned mansions, Spanish moss, and moonlight-and-magnolias vibe, seems an unlikely epicenter for a countercultural explosion, but it has been hippie heaven ever since the Allman Brothers breezed into town, slinging their axes and trailing long, cornsilk hair. Graying ponytails on men still abound, as does cannabis.

The hedonistic Capricorn era, from 1969 to the late 1970s, was Macon’s Camelot, and when it faded, the city struggled to define its identity. One civic motto was “Sherman missed us, but you don’t have to!” – an oblique allusion to meticulously preserved antebellum architecture that escaped some visitors. In the 2000s, boosters decided to lean into everyone’s primary complaint with “It’s hotter here!” Today, it has settled comfortably on “Where Soul Lives.”

“Whatever the essence of soul food, soul ties, soul music, is – that’s Macon,” says Lisa Love, director of the Georgia Music Foundation. “It’s raw and unvarnished and imperfect, but that’s fertile ground for creators and characters, and Macon’s long been a wellspring for both.”

The downtown that languished in the doldrums of urban blight for years has sprung to giddy new life and now claims a 98 percent occupancy rate, with the addition of an estimated 2,000 loft dwellings. They have attracted young, sleek scenesters, who gather for drinks on the new rooftop bar, called simply “45,” and dine at high-end farm-to-table restaurants.

“I left Atlanta to come here, where a typical rush hour is only 15 minutes,” says preservationist Ennis Willis. “People who live in Atlanta think the only other worthwhile places in Georgia are Savannah and St. Simons and that the rest of the state is just a vast wasteland of rednecks and pottery. That simply isn’t true. Macon is exploding with energy.”

A prime mover in this renaissance is The Moonhanger Group, headed by native son Wes Griffith, which has purchased, one by one, several dilapidated music landmarks and restored them to their vintage glory. In 2020, the group teamed up with Mercer University to bring back Capricorn Sound Studios, where artists can use original analog equipment while channeling Duane Allman, or pioneer something new, amid the shag carpeting and groovy, psychedelic art.

At its interactive museum, visitors can listen through a vast digital archive of music recorded there. A stone’s throw away is another Moonhanger project: Grant’s Lounge. Back in the day, it functioned as an informal, Black-run audition space for the studio, and features a “wall of fame” worth perusing – images of artists in the grip of dreams coming true. Griffith also bought the H&H restaurant, where Gregg Allman wolfed down collard greens to lube his prized vocal cords.

Another revamped stalwart from the 1970s is The Rookery, a restaurant and venue where Tom Waits and Rickie Lee Jones reportedly partied ‘til they passed out.

Whether your interest is music, architecture, or history, the city offers plenty to do on a weekend getaway, usually with some memorable Southern Gothic twist involved. The locals are friendly and notably given to stem-winding storytelling — savor that charming midstate drawl, with its taffy-like vowels and complete absence of the letter “r.” A few options include:

- White settlers only arrived in 1823, but the land along the Ocmulgee River was occupied for more than 10 millennia of continuous human habitation by various groups of indigenous people. They left behind seven mounds, built before 1000 CE, one of which you can enter and sense the eerie, goosebump-prickling weight of time.

It was the site of the largest archaeology dig in American history, yielding three million artifacts. The surrounding historical park recently has been expanded to create the first National Park and Preserve in the state of Georgia, enlarging the current 700 acres to nearly 3,000.

The Muscogee (Creek) Nation was the last group to occupy the riverbank, until Andrew Jackson forced them West.. Their descendants have not forgotten their homeland, though. The Nation has just dispatched a new advocate, Tracie Revis, from Oklahoma to Macon to strengthen ties between the eastern and western communities and to improve interpretations of this sacred space.

“I grew up hearing stories about our homeland,” she says. “I believe there has been unintentional misrepresentations of our past, politically and culturally. My move to Macon is to help bridge the connection back to the culture and the tribe.”

Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park will host the Annual Ocmulgee Indian Celebration September 21-22, one of the largest gatherings of its kind.

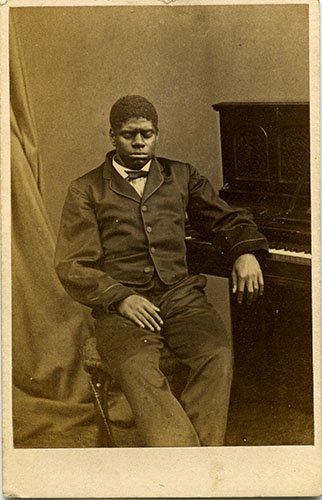

- The sign on the instrument says, “Do not play Little Richard’s piano. He will know.” It is one of hundreds of artifacts at the Tubman Museum, among the country’s largest museums dedicated to educating people about the art, history, and culture of Black Americans. A detailed mural explores Black history in general, and Macon’s African-American history in particular. One touching exhibit is the uniform of Rodney Davis, who received the Medal of Honor. “We’re showing history though African-American eyes, but it is history for everybody, says executive director Harold Young. The Tubman also engages the community with arts-related events, including storytelling, movie nights, and a Pan-African Festival.

- The crown jewel of Macon’s historic district is the Johnston-Felton-Hay House, more commonly known as just the “Hay House.” It is 18,000 square feet and 26 rooms of Italian Renaissance Revival opulence. “We’re in a constant state of restoration,” says Willis, who is executive director. Magnate William Butler Johnston married Anne Clark Tracy, a polished woman from a prominent Macon family, and the two embarked on a lengthy honeymoon in Europe, where they collected fine porcelains, sculptures, and paintings as mementos of their Grand Tour. Inspired by Italian architecture, they constructed their home, which was finished in 1860. It would have made a rich target for Gen. Sherman on his wrathful “March to the Sea,” but he famously missed Macon.

Photograph by Jason Maris

Photograph by Jason Maris Photograph by Jason Maris

Photograph by Jason Maris