Any writer would have to strain not to sentimentalize Blind Tom Wiggins as rhapsodically as he played the piano.

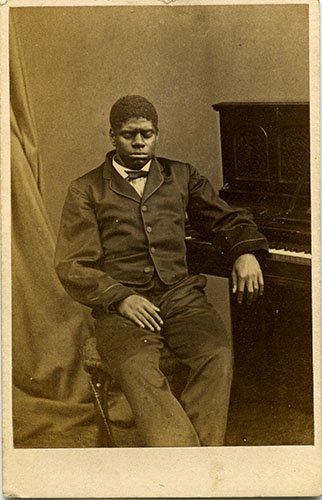

In one of the world’s great underdog stories, he was born sightless, enslaved, and presumably autistic in 1848 in Columbus, Georgia, but he began playing the piano at age three, eventually becoming one of the 19th century’s most celebrated musicians and the first African-American to perform at the White House. A savant with an attachment to the ivories so consuming and rapturous that his hands had to be pried from the keys and distracted with sugarplums, he functioned as a sonic mirror, replicating, note for note, whatever euphonies swirled around him, from trains and birdsong to oratorios and concertos.

One account in The Washington Post describes a stormy night when the prodigy’s owners were startled to observe the child striking chords “until he had produced the exact harmony which he sought, then, springing from the piano stool would grope his way through an open window onto the veranda and, placing his ear close to the gutter, which extended along the side of the house, listened intently for a moment. Having caught the tone desired, he would hurry back to the piano and, after a few trials, reproduce it with wonderful accuracy.” These labors resulted in one of his most popular compositions called “Rain Storm.”

Tracing his biography through reviews, playbills, and other commentary, Deirdre O’Connell, an Australian documentary maker, reconstructs the life of this enigmatic musician with lyricism and annotated thoroughness. Her gimlet-eyed skepticism of certain narrators salvages the dignity of Wiggins from the exploitative hucksterism and ugly social Darwinism of the times as he was shuffled from master to unscrupulous manager. The grounding of her scholarship, though, does not prevent The Ballad of Blind Tom (The Overlook Press) from soaring into a dizzying aria, inflected by field hollers, the natural world, and the poetry — and rivening political bluster — all around him. In fact, it only affirms the marvel of his genius while placing it in the context of two exceedingly peculiar institutions: slavery and the culture of celebrity.

According to rural folkways, babies can be “marked” in-utero by a traumatic event that indelibly stamps them with a defining characteristic. Wiggins’ mother, Charity, attributed his gift to a black marching band that upheaved her soul when she was pregnant, and other enslaved people reverently diagnosed him with the “second sight.” Nevertheless, as a blind “runt,” Wiggins seemed useless to his master, who wanted him dead. Fortunately, another planter, Jim Methune, when beseeched by Charity, purchased the enslaved family on the auction block. Baby Tom was stashed in a box for a couple of years while his mother worked, and some theorize that sensory deprivation fostered his echolalia, but the more popular theory is autism. An unruly Tom could repeat an overheard, 10-minute, adult conversation, but he communicated his own wants and needs in grunts, whines, and tugs. “People on the autistic spectrum struggle to assimilate the sensory information bombarding them and many engage in repetitive behavior to deflect the overload,” O’Connell writes. “Music seems to have offered Tom this type of escape.”

Once the Bethunes realized they possessed a lucrative sideshow, they took him on the road, marketing him simultaneously as a Mozart wunderkind and “idiot Congo boy.” Reviews typically describe a blank-faced “baboon” lumbering toward the keyboard, only to produce a transcendent sound that transfigures his mien, and his stupefied listeners, with “ecstasy.” In fact, the words “ape” and “ecstasy” twine throughout this text, in which triumphs are always undermined by cruelties — and vice versa. One observer wrote: “We could plainly see, dancing in and out of the rose trees, a dark figure, leaping from bush to bush in perfect ecstasy and abandon. Knowing that Tom’s inspiration was upon him, we waited for his next move. He tumbled into the room: a confused mass of head, hands and feet, and only having partly regained his perpendicular, he announced: ‘I will now tell you what-what that stars have said to me.’ Seating himself at the piano, with a prelude of most exquisite chords, he suddenly burst into such brilliant, such wildly gay, at one moment, and at the next such heart-breaking melodies as never before or since.”

Wiggins liked to hurl coins into the fireplace, so predictably he was cheated out of the fortune he earned, the equivalent of $5 million. He no doubt had little understanding of politics, either, but he could recite the podium-pounding speeches of Georgia secessionists down to every gasbag mannerism, and his mimicry of musketry and martial marching, which produced a composition titled “The Battle of Manassas,” was used as Confederate propaganda.

“Blind Tom” appears in the writings of Mark Twain and Willa Cather. Along with his repertoire of classical masterpieces, soundscapes, hymns, and minstrelsy that was said to “out-jump Jim Crow” himself, another part of his shtick, if you could call it that, was to stand on one leg and leap across the proscenium while howling along with the audience. “The American stage had never seen anything like him,” O’Connell writes, and never will again.

Rumored to have perished in the Johnstown Flood, Wiggins made a brief comeback in vaudeville before dying of a stroke in 1908. He was buried in an unmarked grave in Brooklyn. A daughter of his former master tried to arrange for his re-interment in Georgia, but no one is certain today of the location of his remains. Like most virtuosos, Blind Tom deserved better management, wiser critics, and a more enlightened audience. But he trumped them all with his enduring compositions, and, yes, his “ecstasy.” The stars do not speak to everyone.